‘Financially Hobbled for Life’: The Elite Master’s Degrees That Don’t Pay Off ($) by WSJ journalists Melissa Korn and Andrea Fuller is an excellent article in data journalism. The best works of journalism identify and raise big questions more often than resolve issues — this one surely does.

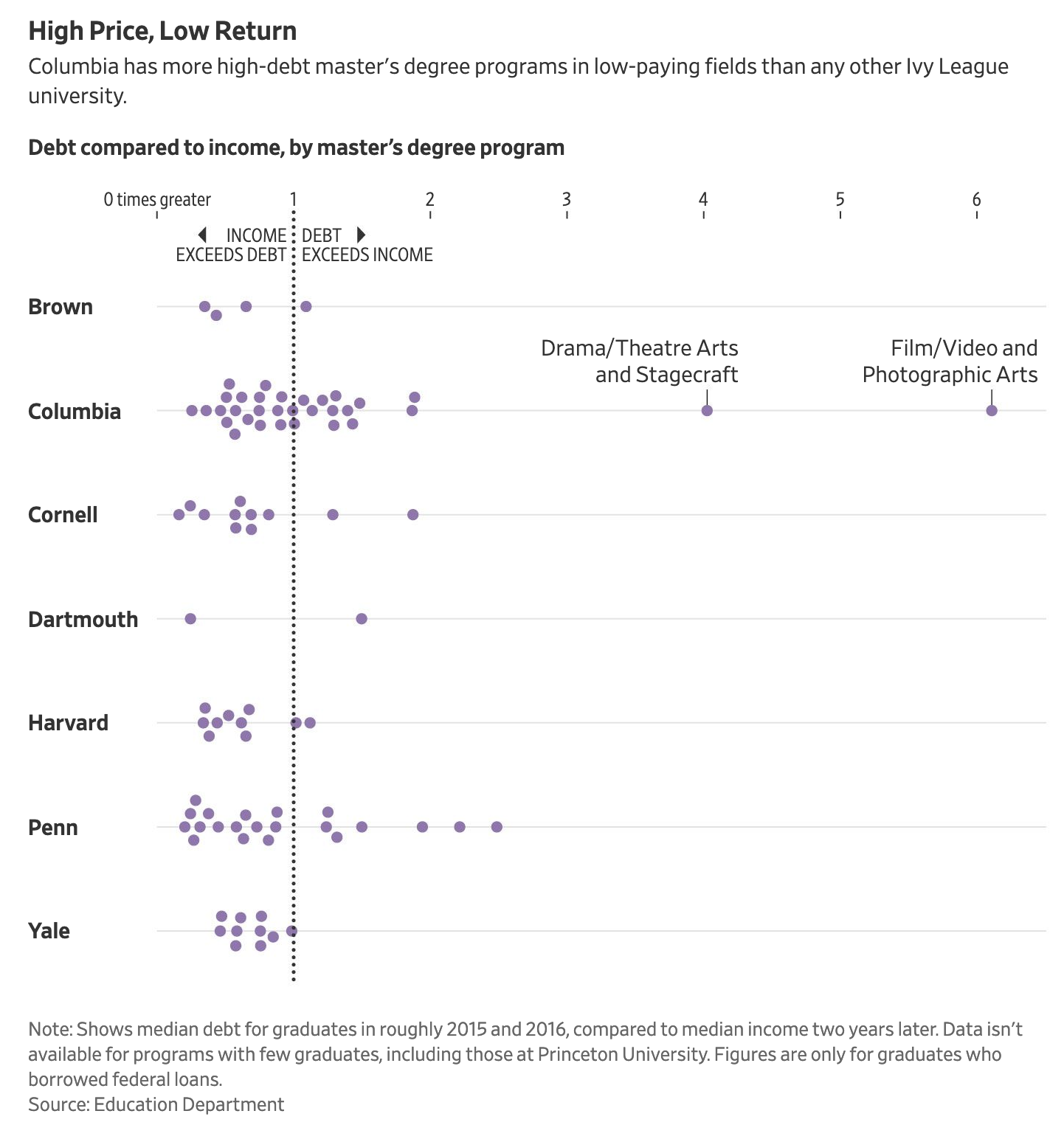

Using Education Department data, they study how elite universities have awarded thousands of Masters’ degrees that do not provide enough career earnings to pay down the federal student loans. The article focuses on elite universities (particularly the Ivy League schools, except Princeton whose programs are very small to do data analysis). A significant proportion of the article focuses on Columbia University, and particularly, two programs — (i) Drama/Theater Arts and Stagecraft, and (ii) Film/Video and Photographic Arts. As you can see in the picture below — they are clearly outliers based on the Debt/Income Ratio.

At this point, a somewhat (obvious) disclosure: I am a faculty at Penn which is one of the Ivy League universities shown in the data above.

It is not just the Ivies alone that have this problem. Such degrees hold sway in other elite schools such as NYU, Northwestern, and USC:

At New York University, graduates with a master’s degree in publishing borrowed a median $116,000 and had an annual median income of $42,000 two years after the program, the data on recent borrowers show. At Northwestern University, half of those who earned degrees in speech-language pathology borrowed $148,000 or more, and the graduates had a median income of $60,000 two years later. Graduates of the University of Southern California’s marriage and family counseling program borrowed a median $124,000 and half earned $50,000 or less over the same period.

As a first-generation college and the first in the family to go past high school, I could go to my top choice university only because of scholarships and the promise of a better future. For both undergraduate and graduate school, I relied on a combination of income from summer jobs, stipends, and finally, massive high-interest borrowings (not federal loans) way above my family’s capability to repay, to cover expenses.

So given the history of days of my youth under debt, and now a faculty at an Ivy-league institution, this issue is personal to me. Hence, I can’t help reacting with some inputs.

—

Revenue Centers.

I think that many associated with the programs and universities know that these future median incomes are low. The article clearly points out that some faculty members and students have clamored for more help.

“The New York City university is among the world’s most prestigious schools, and its $11.3 billion endowment ranks it the nation’s eighth wealthiest private school.

“For years, faculty, staff, and students have appealed unsuccessfully to administrators to tap that wealth to aid more graduate students, according to current and former faculty and administrators, and dozens of students. Taxpayers will be on the hook for whatever is left unpaid.”

So, what’s happening?

First, I think programs are like busy train routes. The railroad is owned, and prices are a local monopoly. They only stop when they become “unprofitable” and it looks like these programs are profitable for the school. It may boggle our minds to think of universities as profit centers but that’s definitely a part of the issue at play here. It is also clear from the article that there are many students who pay their way through while a substantial number of students are on federal loans. Once the program is set up — it burgeons with administrative costs (new people need to be hired as faculty famously hate administrative duties). Because of such factors, these programs run at surprisingly low profits, as costs expand to meet revenues (which also keep increasing).

Strictly speaking, these are not Baumol costs, but costs associated with the non-monetary “servicization” and the additional bureaucracy that goes on in schools.

This problem is further exacerbated by two factors. The tuition is collected “up front” and there is very little recourse action for students who don’t find the program useful. Often, loans are private student information that is “hidden”. As a teaching faculty, I don’t know which student is on scholarship/loan when I teach a class. I certainly can’t tell.

Stardom and Medians.

An inconvenient truth is that we love outliers and build our narratives around them. Universities love their Nobel laureates, prize winners, and famous graduates. (I am guilty of being trapped in this thinking as well. At grad school, I knew that the actor Ted Danson graduated from Carnegie Mellon University Drama School. Even today, I still don’t how much the fine arts program graduates earn).

No one knows the median until we look carefully at the data. Every year, I am sure a number of waitresses in the Midwest escape boredom and run away to Hollywood in hopes of becoming the next starlet. In their aspirations, they could be the next Winona Ryder. But, tinsel wood is full of family connections and many broken hearts (and usually, both in the same family). What would be the median income of all people who left the Midwest for Hollywood?

No one is shocked at this kind of social cost because at a visceral level we all seem to accept the notion that the film industry is a slice of the old Wild West. At its worst, Hollywood is a breeding ground of nepotism. At its best, it is an unfair beauty contest. Most new arrivals scrape the tables at restaurants and don’t make it big. Some lucky winners become famous. Of course, the utter averageness of the winners, in terms of both beauty and talent, only continues to churn this treadmill, because “hey, you can be a star, too”.

But Education was not supposed to be this way.

Educated Upper Class.

Education is often the differentiator between the haves and the have nots in America. In fact, there is perhaps no divide bigger than the educational divide in the United States. Doctors marry doctors and PhDs marry other PhDs. Their precious, precocious children become educated graduates. This kind of success with a head start and easy career layups at an alarmingly increasing frequency, make universities look like inherited fiefdoms. So, to feel better, to find the balm of equity, we all look elsewhere. Where is the grit? Where is the dynamism? Where then do we find evidence in education is meaningful?

It is in this world, the whole “first-generation” — obscene and grotesque in its self-congratulatory aesthetic — is propped up. Going to college makes us not only successful but also better than our “uneducated” progenitors.

It is a sleight of hand without an equal: Substituting Earning a Degree for Earning an Education.

Indeed — the averageness of the successful achievers is patent to everyone watches. We are told that guys of average intellect are deep thinkers and geniuses as they get appointed to lifelong federal positions because they earned their degrees at top schools. We are told that they are creme de la creme. We are told that so-and-so brilliant scholar topped their class at Yale, even though the programs that they allegedly topped, don’t rank their students.

Schools and Universities are the ultimate power plays in our world: we often use them as cudgels to dismiss smart people who graduate from HBCUs and schools in the Midwest. It is not a coincidence that Ivies don’t exist in Midwest or deep south.

I see the comments sections at WSJ being vituperative at the “dumb choices” of graduates who sign up for these programs and end up in debt. The tuition for these programs has gotten way too high, but I am afraid this is incorrect to blame it on students.

Education makes people better, even if it doesn’t always make them well off.

But we know that belonging to an educated class brings respect, ‘street cred’ and opens roads to financial success for ourselves and our children. So as a student who graduated from a state school, what are your choices to climb the class ladder? If you don’t invest in yourself when you are young, who else will invest in you? This is the dream that education offers.

Just like the good-looking person from Midwest, looks at the average starlet, and thinks “I can do it, too”, people who go to colleges carrying debt are not blind, but hopeful. Disappoint hangs around the corner where they live, the universities are a golden ticket.

They look at the utter averageness of people who boast of fancy degrees and high connections, being appointed to top posts. The best ones that believe in themselves think “I can do that, too”.

Both Hollywood and schools are similar in truly believing in the dreams that they sell. Universities create these programs because they believe they make people better, just as Hollywood stars believe they are all in it for the art. These endeavors are deemed worthy because the true costs are unknown.

So seeing the data is an eye-opener. This kind of data is like a speed breaker and a stop sign on the downward road to broken dreams. It makes us pause and think about our downward hurtling.

Some Solutions (Thinking Aloud)

What we should do? I have a few thoughts.

1. Cap the loans. Currently, the federal Grad Plus loan program has no fixed limit on how much grad students can borrow. This seems to include tuition and living expenses. I think it is reasonable to cap this using some LTV. There should be a serious cap measure that requires schools to “pitch in” with stipends and scholarships more than the current debt counseling.

2. Tuition Reform. I think that programs should have more “skin in the game”. Instead of a lump-sum payment for the entire tuition fees — a part of the tuition should be tied to the proportion of income, like some ed-tech startups are trying to do.

3. Create Dual STEM programs for non-stem undergraduates. It is not coincidental this is not an issue for STEM-type programs. As anyone would attest getting into stem programs at the master’s level is difficult. What should people who are enrolled in the program do when they are at school? Perhaps learn other technical tools when at school on a loan?

Postscript: MBAs for the win?

Finally, I want to praise the often derided MBA programs. To the extent we want educational degrees to be practical and self-paying for those who don’t want to go down the “research” path, MBA programs are closer to the ideal. They teach “real skills” like managing an accounting book, reading financial statements, understand tax structures, and thinking about softer skills like people management. Although they try hard to be STEM-type programs — out west, people often make fun of MBA programs for this — they teach life skills and peer learning. In fact, more university programs should be like MBA programs that teach new skills and livelihood.

Another Update:

I commented how often people in the “Revenue Centers” point that people know how these programs are and that as the tuition is collected “up front” and there is very little recourse action for students who don’t find the program useful. Indeed, an astonishing Twitter thread by James Stoteraux only shows that the problem is even deeper. There are known errors of commission. Time for tuition reform.