For long time e-commerce and operations observers, it was no surprise that Amazon was opening its “shipping” business: It was as predicable as a bowling ball on the lane slowly rolling to the pins. Much earlier, in 2014, Amazon had invested in a British shipping firm, Yodel. In 2016, Amazon had purchased a 25% stake in the French parcel Delivery company Colis Prive. Through FBA (Fulfillment by Amazon), Amazon already handles “logistics and shipping” for third party sellers – currently at 51% of all sales units (in 2017 Q4). It has been at that proportion for several quarters now.

So no surprise, really. However, let’s talk about who is absolutely critical for Amazon to compete with UPS and FedEx.

Compared to the news covering Amazon’s “decimation” of grocery retail with the acquisition of Whole Foods, and the “disruption” of the health care insurance market, the coverage of shipping has been relatively sedate. Much of relative stability, despite the share price drops, was due to the non-responses of UPS and FedEx. Both firms treated the news without surprise, as a natural culmination of events that were already set in motion like the bowling ball.

However, in the media, there has been allusion that that shipping is a low-margin business (which it is), and hence is relatively “safe” from Amazon (which it is not).

Indeed, shipping is a low margin business mainly because of big setup costs in labor and vehicles, highly variable marginal costs (fuel), and heavy competition. Otherwise, lovely Operations Research focused approaches such as UPS trucks taking routes without making left turns would not be principally important to the optimization of shipping operations.1 Saving every cent is critical in a low margin business.

But, a low-margin segment is precisely the market that Amazon loves to study, wait-and-move in. They have done it now. I am saying nothing new here, as this approach is definitely not a surprise.

Hear it from Jeff Bezos in 2011 –

There are two ways to build a successful company. One is to work very, very hard to convince customers to pay high margins. The other is to work very, very hard to be able to afford to offer customers low margins. They both work. We’re firmly in the second camp. It’s difficult—you have to eliminate defects and be very efficient…

Amazon is in the business of skimming the margins in every industry. Armed with a willingness to forgo short term profits, backed by an extraordinarily patient investment class, Amazon can channel all the margins from AWS, into the last mile shipping to play the long game.

Furthermore, Amazon which is currently spending 13% of revenues on shipping and logistics, must be seeing some scale of economies in specific geographies to go it alone.

Amazon Flex is not the magic bullet

Some articles I read argue for Amazon’s ability to compete based on Amazon Flex1 – an Uber-type army of independent shipping contractors working for Amazon.

Such analysis gets it exactly backward. I would argue that Amazon Flex is a dilution of Amazon’s service guarantee. I wrote about service failures and trust-in-service path in the context of Amazon Key.

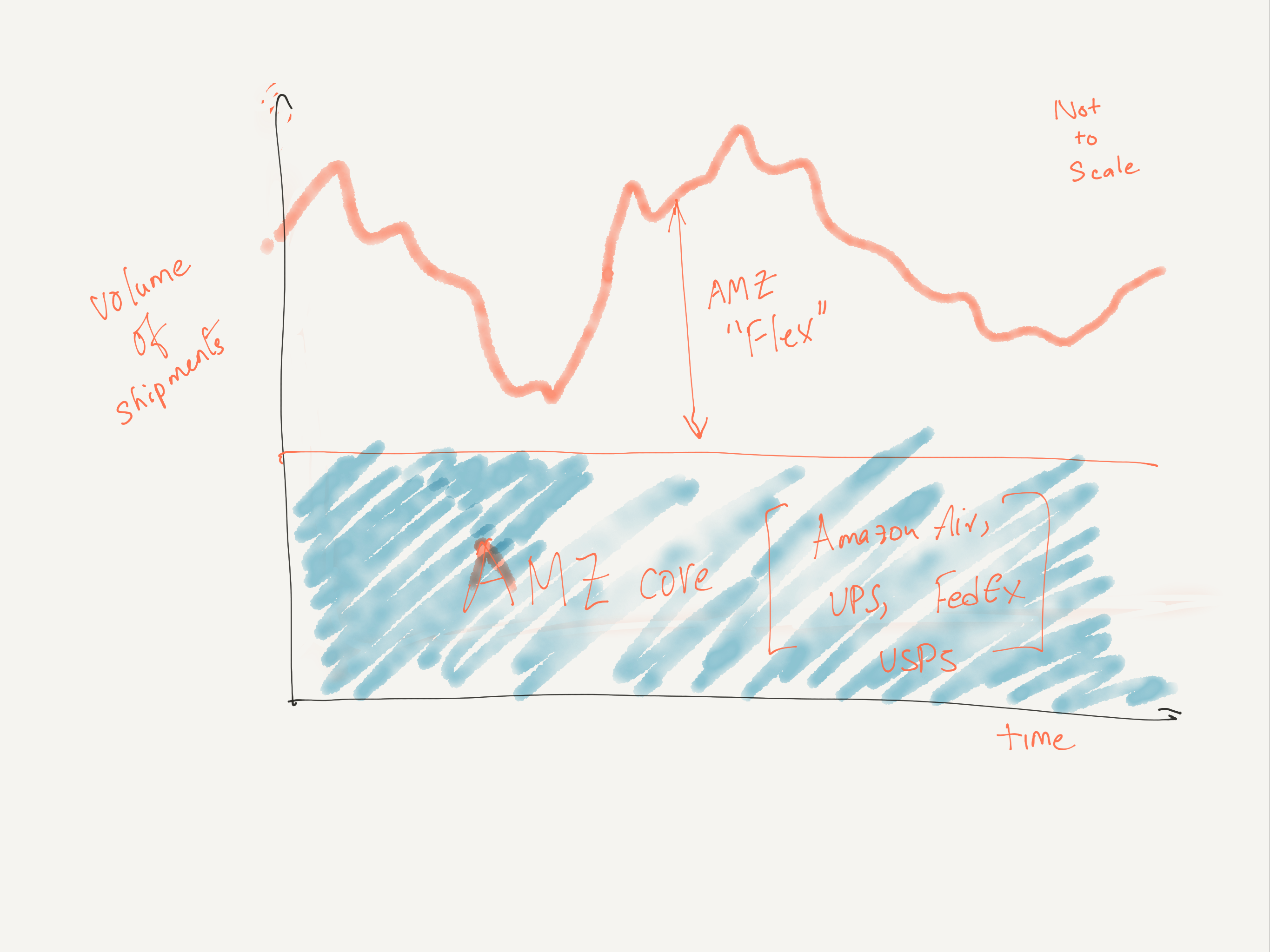

The main point is that “Amazon Flex” is not the “core” of their shipping business. Amazon Flex exists to tackle short-run volatilities in shipping volumes. It is a backup plan if your goal is to provide high customer service. See the schematic figure below. Amazon Flex can’t be the main strategy as it is problematic in two ways: (i) it necessarily invokes the possibility of poorer service, and (ii) service provision during demand spikes is expensive.

Note that my argument does not depend very much on how much of Amazon’s business is handled by Flex — this data varies quite a bit geographically.

Long Term Partners

The blue area in the chart below is the fraction of steady shipping volumes through low-cost, long-term contracts with UPS, USPS, and FedEx and vertically integrated Prime Air, a number of small shipment companies like Lasership, etc.

Effectively, the parcel business is highly competitive (as pointed above), and needs to be cheap, as Amazon effectively is trying to keep margins low and volumes high and steady. It is clear that opening a shipping competitor to customers, will suppress the volume of shipments handled by UPS and FedEx. Amazon is an e-commerce giant, but still a small player in the parcel shipping business. (UPS does not report the fraction of revenues that are Amazon shipments — the fraction likely does not exceed 10% of the total revenue pie. Absent accounting wizardry, 10% should/ would trigger reporting).

So, the entity who is absolutely critical for Amazon to compete with UPS and FedEx is

United States Postal Service.

This point has been previously argued by Josh Sandbulte in his WSJ editorial. Sandbulte estimates that each box gets a $1.46 subsidy. It would be nice to track percentage subsidies, which I couldn’t get to. (Note: WSJ competes with Washington Post which owned by Bezos. Despite incentive misalignment, the point that there is a transfer of subsidies is a fair one).

USPS, scaffolded by the taxpayers, is the moat3 that protects Amazon by securing deliveries of a large volume of its “steady” shipping. With the new shipping spinoff, USPS’s position has become more valuable for e-commerce.

Can Amazon do without USPS? I doubt it. (It is clear that USPS also needs Amazon for non-operational reasons). Aircrafts owned by Amazon only help with shipping within the fulfillment centers, trucks help with dense neighborhoods, but for the last mile deliveries everywhere, they need a steady hand —

— undeterred by neither snow nor heat nor gloom of the night.

Who else, but USPS.

In the age of e-commerce, USPS could be re-organized to make a comeback, as large fixed capacity investments align well with delivering fast services. In other words, low labor utilization is not a major deficiency in fast last-mile deliveries. I will revisit this point extensively in a future blog post.

This post belongs in a series of posts focusing on Last-Mile Operations. If you love the blog, please subscribe.

Notes:

- UPS trucks don’t turn left. Not a myth. (Obviously, this holds only in nations where trucks drive on the right-hand side). Although this is a vehicle routing problem, my understanding is that financial savings are from fuel usage than distance per se.

- Amazon Flex — I ignored the legal issues associated with deliveries using temp workers.

- Moat isn’t the right analogy here – It is more like commandeering the serfs from the village around the moat, and outside the castle walls.